- To See In The Dark

- Posts

- Murder in Minneapolis

Murder in Minneapolis

What Happened and What To Do Next

Once again. In the wake. This time, Minneapolis. It’s all too familiar. I go back to Blair Peach, killed by London police in 1978, later memorialized by artist Isaac Julien. We remember Rodney King in 1991, Eric Garner from 2014 and of course George Floyd in 2020, murdered just a mile from where Renee Nicole Good was shot down yesterday. All these videotaped killings and assaults by police come back. As they should.

Let’s be mindful that there are those for whom Renee Nicole Good’s senseless murder will be a first—young people, recent immigrants, people in the Midwest. It’s upon us to do the work at hand for them, even as we can also feel sick and tired of so much violence over so many years. The “we” I’m using here means simply those who read this newsletter, who, I can tell you, are very diverse in backgrounds and ethnicities but not those for whom this is a first.

Let’s check in with ourselves. What histories need to be deployed? What do we call what is happening now in relation to those histories? And what unfinished business has been neglected that should now be attended to?

Forensics

You’ve seen it. You know what you saw. Renee Nicole Good was asked to move her vehicle, which she had apparently stopped to make a video. First she waves the cars with sirens through. When masked men jumped out of one and attempted to force entry to her car, she slowly backed up to make a careful three-point turn. Whether she was aware of the man grabbing her door can’t be known, but the right turn of her wheels is evident. Her maneuver took her safely past the man to the left of her windshield. He opened fire and placed three bullets in her car, killing her.

Perhaps you, or someone you know, thinks there is room for doubt, that you cannot quite see where the shooter was in relation to Good’s car. Look then at the bullet holes. The first bullet enters the bottom left of Good’s windshield. Simple geometry indicates that the shooter was safely away to the side of the turning car. He could not have been standing in a place where he might have been hit. Go and stand next to a vehicle, you can see this.

The next two bullets entered the driver’s side window, evidence that the car was safely turning away. Long ago, US philosopher Charles Sander Peirce used the bullet hole as the definition of what he called the “index”—a sign pointing to a real experience. These bullet holes tell the story of an unnecessary murder. Prior to opening fire, the shooter is documented as filming Good’s car. With her license plate, an arrest would have been easy to make, if required.

Violences

What actually happened here? The function of the police is to use the monopoly of violence claimed by the settler colonial and imperial state against its own subjects. The murder of Renee Nicole Good took place five years to the day since the January 6th insurrection declared open civil war on behalf of white supremacy and racial capitalism, connected back to the Confederate insurrection and across to the Israeli racial colony by means of flags and statements. That the murder took place near the spot where George Floyd died was entirely intentional. Someone was going to get hurt yesterday. It was Renee Nicole Good but it could have been anyone in the area.

In New York, a woman known only as the polka-dot lady flipped off ICE agents making a racially-motivated raid last October on African traders on Canal Street, a few hundred yards from where I live.

In December, ICE dragged a woman through the snow in Minneapolis, only to be pelted with snowballs by other protestors, leading to her unarrest.

At least nine people have been shot by ICE since September, all accused of trying to ram them with their cars, when video clearly indicated otherwise. it happened to Silverio Villegas-Gonzalez, murdered by ICE in September 2025. It happened to Marimar Martinez in Chicago in October 2025. Shot multiple times by a Border Patrol agent, all charges against her were comprehensively disproved. Martinez survived multiple gunshot wounds.

By the same token, the denials and deflections come pre-written, as they have since the era of Jim Crow. Any state agent whatever will always say that they were in fear for their life. Darnella Frazier’s video of the murder of George Floyd was able to evade this pre-prepared lie because it was so evident that the supine Floyd poised no threat whatever to the sadistic Derek Chauvin.

Ubiquitous cell-phone video has changed the stakes. In 2025, industry sources claimed that 92% of all internet traffic was video (both short and long form), seen by over 90% of users every week. Online video is watched for over 20 hours a week on average in the US, three-quarters of which are accessed via mobile devices. It is high quality, without the fuzziness of the “poor image” from the 2000s.

“Believe what you saw,” said Chauvin’s prosecutor. The jury did, not because they had a naive faith in the visual image, but because of their long experience with short vertical video. From that long watching, audiences know that any “public” or national “imagined community” is always already segregated, exclusionary and hierarchical, a fantasized projection onto the walls of separation that constitute settler colonialism. The difference in that case was the jury was willing to say so publicly.

Even the New York Times, always prone to defend police, has looked at the videos of Renee Nicole Good’s murder and seen that the police are lying. Actually, the headline says “videos contradict administration account,” which is as mealy mouthed a way they could have found to say it.

There’s work to be done by critical visual activists. The existing scholarship on such digital “visual artefacts” is very different from that used in visual culture. Quantitative software-based tools have been made to analyze the now-ubiquitous digital moving image. Such methods render images into data points and create visualizations of their use, relying on a large set of visual materials. What matters in these cases is usually a single video, or small set of videos. Without rejecting digital methods, research into these video sets needs to work across platforms, using intersectional approaches and multiple forms of digital and visual analysis.

Histories

This murder was not an unfortunate event, a contradiction within an otherwise orderly society. It is structural and systemic, a central component of settler colonialism. Here I will bookend the longue durée of these practices, without pretending to be exhaustive. Armed state-sponsored violence against migrants, whether forced or voluntary, was foundational to white settlement in the Americas. It was and remains, an act of genocide.

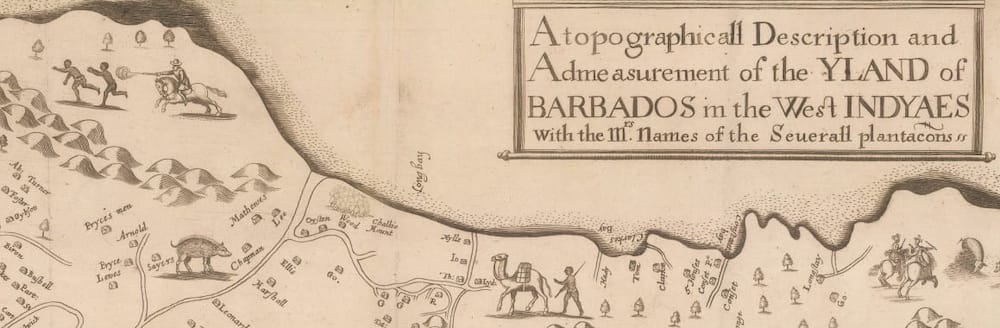

Armed settler violence in Ligon’s 1657 map of Barbados.

In 1657, the first printed map of Barbados, then the greatest wealth-producer in the British empire, was made by the Englishman Richard Ligon. In the detail above, you can see at top left a white man on horseback chasing two African fugitives and firing his gun at them. On the right, another set of such police patrol, armed with the yardsticks used by plantation overseers. Still a third can be seen in the middle of the map (not visible in the detail) next to the legend: “The ten thousand acres of land which belong to the Merchants of London” (spelling modernized). This is a map of racial capitalism.

Jump cut to the modern. In the 1944 Antifascist Civil Rights Declaration, fair employment in industry and the military were connected to legislation against antisemitism, against the “incitement” of racial hatred, and to the abolition of Jim Crow. No such act was passed.

Civil Rights Congress, “We Charge Genocide” (1951).

Accordingly, the Civil Rights Congress filed a petition with the UN in December 1951 against “genocidal jimcrowism,” using the 1948 Convention against Genocide. The petition highlighted the understanding that genocide targets “in whole or in part, a national, racial, ethnic or religious group.” The petition was also published in book form as We Charge Genocide (1951). Petitioners included many Jewish people, alongside such Black luminaries as W.E.B Du Bois, Claudia Jones and Paul Robeson.

Edited by William L. Patterson, all the evidence cited came from after the end of the Second World War in 1945, once the term “genocide” had been coined by Rafael Lemkin. Further, a change had come in the US: “Once the classic method of lynching was the rope. Now it is the policeman's bullet.” The indictment was detailed and extensive. Entry after entry read like this: “Week of October I6 [1948].-DANNY BRYANT, 37, of Covington, Louisiana, was shot to death by policeman Kinsie Jenkins after Bryant refused to remove his hat in the presence of whites.” What happened in Minneapolis is still part of that genocide.

Monumental

Immediately following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, two related courses of action were taken. People began removing monuments to white supremacy and colonial hierarchy. And they called for the defunding of the police, the abolition of the genocidal regime that has persisted in the Americas for so long.

That business remains unfinished on both fronts. The artist Kara Walker is currrently showing a work entitled Unmanned Drone (2025) in Los Angeles. It has been made by cutting up and reassembling the statue of Confederate general and slaveowner Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson from Charlottesville, VA. The statue had stood close to the infamous one of Robert E. Lee, the site of the Unite The Right rally in 2017, and finally melted down in 2021.

Kara Walker, “Unmanned Drone” (2025). Photo: Frederik Nilsen

This remade form, a dérive from the readymade, connects the genocide called Jim Crow to that unfolding today. While all the critical attention has focused, perhaps inevitably, on the legacies of 2020, Walker named her work “Unmanned Drone.” Just as the Confederate statue was an infrastructure of genocidal US white supremacy and surveillance, Walker prompts us, so too does the drone perform these functions in Gaza and other occupied territories.

Just this week I saw testimony from a pediatrician who had worked in Gaza. Time and again, children told him that after a major attack, whether by missile or bomb, as they lay there, IDF drones came to seek them out. And shoot them.

Whether for fear drones might become a new assassination method, or to remove another means of documenting state violence, the Trump administration has banned the most popular drones made by Chinese company DJI, along with a range of other small drones.

Walker’s anti-monument shows that, to reuse the name of a New York-based direct action group, all your genocides are connected. Writing with Nika Dubrovksy, anthropologist David Graeber elaborated: “Police are the guardians of the very principle of monumentality—the ability to turn control over violence into truth.” Police and monuments stand for the purported “truth” of racial hierarchy, of settler colonialism, and of the genocides that enable them.

Work

There are so many ways to take action against the murder of Renee Nicole Good and all the many thousands gone before her. You know this because you have already done it before but you, we, left off. We failed to connect. We spent more time calling each other out than building a consensus or a movement. Let’s acknowledge this, forgive but not forget, and resume.

Here are some thoughts to keep in mind.

If there is one act of genocide, there will be many.

If there is one monument to white supremacy and colonial hierarchy, the practices they commemorate will continue.

All the monuments must (still) fall.

We make each other safe, yes. That can only fully happen when weapons are extremely hard to obtain and when the present rampage of state-sponsored violence has been curtailed.

It will take a movement.