- To See In The Dark

- Posts

- Omnicide Or Communism?

Omnicide Or Communism?

Six months after To See In The Dark

To See In the Dark has been out for six months now. In that time, things have become better and worse. Better only in the limited sense that the genocide is too visible to deny. Worse, much worse, in terms of the continuing catastrophe in Gaza and its expansion regionally and globally. Who could have imagined tanks firing on starving people coming in search of food?

The terms of analysis in the book have become more pertinent in that short period, even as it now seems clear to me they were understated. Now I would simply say: white sight is genocide. Whereas, to see in the dark is communist.

It’s not (just) a struggle in political economy and imperial culture. It’s about competing ways of (not) seeing. These ways of seeing are politics in the era of distributed war and ubiquitous social media.

Rosa Luxemburg once posed a choice between “socialism or barbarism.” Today, 625 days since October 7th, it feels closer to “omnicide or communism.” The rest of the post is what I mean by that.

Omnicide

My book began by recalling the moment in March 2024 when feminist activist and thinker Silvia Federici told a packed house in New York : “Palestine is the world.” Palestine was exemplary of the world before October 7, epitomizing the global majority that is young, lives in cities and has access to the Internet. That is to say, when we say “free Palestine” we say “free the world.”

What does it mean to say “Palestine is the world” today, after more than 50,000 deaths, projected “indirect” deaths close to 200,000, the imposition of famine on those still living in Gaza, and the expansion of the “Greater Israel” war to Iran? Palestine remains exemplary. It enables us to see the racial patriarchal capitalist world as it is, one constituted by genocide, but also by ecocide, scholasticide and all the other forms of exterminationist killing.

Together this “cidal swarm” constitutes what Waanyi writer Alexis Wright calls “omnicide,” or more exactly “the bloody omnicide... the aftermath, the mess of racism and colonialism, the wholesale disaster of the Anthropocene.” Omnicide requires a multi-faceted, distributed way of seeing, deploying an infrastructure of permanent surveillance. Omnicide is and has been the dominant way of seeing like a (settler-colonial) state.

Neoliberalism liked to pretend that capitalism was rational. Now we see it like Marx in Capital: “Violence is the midwife for every society pregnant with a new one. It is in fact a kind of economic power.” This gestational labor, a violent, fleshly entanglement between capital, gender, and imperial necropolitics, is the war economy constituted by racial capital.

Violence is not a by-product of capitalism, or what the accountants now call an “externality.” It constitutes the capitalism of capital in its never-ending “original accumulation,” once called primitive accumulation. This violence forms what Maurizio Lazzarato calls “war against population” and Zapatismo’s identification of the fourth world war as the war against subsistence. Gaza epitomizes the violence of capital.

White sight is genocide

I want to say more forcefully than in the past that white sight—white supremacy’s way of seeing—simply is genocide. In Abraham Bosse’s 1648 perspective, armed white soldiers are claiming territory, which can be calculated and made into what settler colonialism calls terra nullius, nothing land. All human and other-than-human life in that land is erased. “Seeing” is the name for that genocide. It makes nothing land out of many somethings. When lived experience refuses to accord with this “reality,” the gap was and is closed by violence.

Bosse, “Perspective,” 1648

And so when the IDF drone used in the 1982 invasion of Beirut projects this way of seeing, the actual military name for what it sees in the white rectangles is the “kill box”: anything seen there can be killed, without justification or fear of retribution. But what the perspective soldiers saw were kill boxes, too. And all Palestine—increasingly anywhere there are opponents of Israel—is now a kill box.

Communism

All the space outside the narrow purview of genocidal white sight is the “dark,” the space in which we can do a different kind of seeing. It’s always the majority of the space, meaning that as the Center for Convivial Research and Autonomy (CCRA) put it, we are winning—and they know we are.

Unlike spaces of surveillance, the dark has to be activated. It begins with the refusal of the saturation of everyday life by logos, brands, influencers and all the apparatus of commodity capitalism. That’s easy to say and hard to do—there wouldn’t be an Internet or any platforms if advertising didn’t work.

This activation then enables the recognitions that sustain solidarity, defined by ACT UP chronicler Sarah Schulman as: “the essential human process of recognizing that other people are real and their experiences matter.” Or in my terms, the “right to look”: which I do not have, I give it to you; and if you accept it, so that you look at me and I at you, then something common, better communist, appears between us. It is communist because it cannot be owned or even represented.

This activation creates the popular, majoritarian form of “power,” known as potencia in Spanish and potenza in Italian. Unsurprisingly, you can’t say this in English. Argentinian activist-scholar Verónica Gago defines potencia as “the desire to change everything.”

The “dark” doesn’t operate like perspectival space. It has two common horizons: one is “baseline” communism and the other is abolition.

The anthropologist-activist David Graeber argued that the social is always formed by “baseline communism”—if I ask you to pass the salt, you don’t say “what’s in it for me?” This baseline communism is what Graeber called “the raw material of sociality, a recognition of our ultimate interdependence.” It is more about the social than it is about production. Capitalism is a very bad way of organizing this communism.

The CCRA define conviviality as “the dynamic, collective energy of interdependent community regeneration uninhibited by capitalist command and discipline.” That’s what I mean by (baseline) communism. It has nothing to do with Stalinism.

Abolition

The further horizon of the dark is abolition. In the book, I wrote:

Being anti-Zionist means being an abolitionist. Until the carceral, ethnonationalist, militarized, segregated, settler-colonial state of Israel has been abolished, it will not have been possible to be part of the class “Jews.”

That is to say, insofar as it is intersects with Zionism, Jewishness is a carceral formation. Undoing that formation is the work of anti-Zionism. Some want to make it part of a different Judaism: if it works, great.

Until then, there are multiple horizons within abolition. The reform that improves the conditions of the incarcerated is one. Another is what Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “non-reformist reform,” meaning “changes that…unravel rather than widen the net of social control.” Defunding the police is one such non-reformist reform, which explains the immense resistance to it.

In Palestine, such a non-reformist reform would be the recognition that Palestinians have equal rights to other residents; or a recognition of full legal equality between all persons in Palestine (meaning the repeal of the 2018 Basic Law); or the recognition that the sovereignty of Palestine (or Lebanon, Iran, Egypt or Syria) is equal to that of Israel.

And while it is not often in view, there is the horizon of a Palestine, free from the river to the sea, a concept so unthinkable to settler colonialism that it has been rendered unspeakable.

The Specter of Communism

Just as the space in the dark is not the projection of white European rationalism nor does its time follow the “rational” colonizing measures of Greenwich Mean Time. In the dark, it is the time of the ghost, always already out of joint. While there is no shortage of ghosts in Palestine, the specter in dominance is and was the specter of communism.

This haunted mode of being means modifying the older claim that politics is the intersection of the visible and the sayable into the relation of the visible and the unspeakable, that which creates revulsion and that which cannot be spoken. It cannot be spoken because it is “beyond words” but also because it is prohibited. To see in the dark is to find ways to see, feel, hear and say the unspeakable.

In 1993, the year of the Oslo accords, Algerian-Jewish philosopher Jacques Derrida visited the Spectres of Marx. In 2023, just before October 7th, British Palestinian writer Isabella Hammad published Enter Ghost. For both writers, systemic, structural violences create specters that operate between vectors of the now, as they move in the time-spaces between life and death.

In both these works, Hamlet is in conjunction and conjuration with The Communist Manifesto. The temporality of the communist ghost is the future perfect. As Egyptian-American writer Omar El Akkad has written in relation to Gaza, “one day, everyone will have always been against this.”

The specter of communism comes not from the past but from the future. For Hammad, writing about a performance of Hamlet in the West Bank, the Palestinian is the specter of the occupation: “they want to kill us but we will not die.” As Derrida knew, the specter refuses to die in the name of justice, not law.

Hammad’s novel closes with the occupation firing tear gas and bullets at a performance of Hamlet by the Separation Wall, just as the ghost enters and tells the IDF “I am thy Father’s spirit.” This is a filiation to unravel, a gestational labor to account for, the conjuncture of terror and communism.

Encampment Murmuration

For those of us engaged in education, the baseline for the communism to come is the Gaza solidarity encampment, whose genealogy included Occupy, the Arab Spring, Resurrection City in 1968 and the 1932 Bonus Army encampment. The encampments refused omnicide and opened a communal, convivial time-space for study.

It is not that all future learning will be conducted outdoors in the shadow of genocide. Rather, the encampments showed the pleasure of being and learning together outside the coercive institution of the debt-for-credits machine that the university has become. As Moten and Harney put it, “the weapon of theory,” to be used against efforts to create racialized hierarchy, “is the conference of the birds.”

Such murmurations, “can become a ‘networked pedagogy,’ or temporary autonomous zones of knowledge production.” It’s not our work to build an alternative educational bureaucracy, still less to create all of communism. Here and now, our concern is sustaining a line of flight from the encampment as a site of recognition.

The murmuration sees each other as its condition of existence, not singularly “as,” but in relation and in motion, only as long as the murmuration holds. It is a temporary democracy, held together while each member decides to fly toward the dark of each other’s bodies. The community moves through the body. This communism is a flying in formation, in a changing social formation, in which information is produced but is not the only reason to have a body, collective or otherwise.

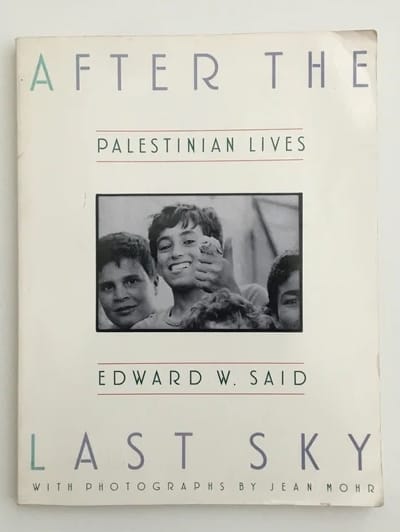

The epigram to Edward Said’s 1986 photographic essay with Jean Mohr After the Last Sky c the poet Mahmoud Darwish:

Where should we go after the last frontiers

where should the birds fly after the last sky?

On the original front cover of the book was a photograph taken by Mohr of young Palestinians with a rescued finch. Goldfinches remain the most popular pet bird in Gaza, where they were regarded as family members before October 7th. The finch looks out at us from its perch on the hand of a smiling young man. As Said wrote, “we [the Palestinians] are also looking at our observers...we too are looking, assessing, judging.”

Since October 7th, we have seen the last sky, over and again. On May 25 at Dar Jacir art and research center in Bethlehem, the Body Watani dance group performed After The Last Red Sky “a performance and ritual gathering to hold the weight of—and imagine healing for—the Palestinian sky.”

This performance understands that the present is not now but after: after the last sky, after the Nakba, after five centuries of violent accumulation. After all that we now know, that capital will subsume every living thing. That leaves us with a choice: continue with omnicide, or start again from the baseline and create a new communism.